Intentionality and Decision-Making in the Senior Team

Effective leadership often comes down to two critical tasks: making good decisions and engaging others to execute those decisions.

While such reductionism can sound simple (or even simplistic), those two tasks can be quite complex. Making good decisions at the upper level requires a deep understanding of how optimal decision-making occurs, as well as the pitfalls that can accompany it. Having a poor process can significantly impact morale and performance. Our colleague, Steve Madenberg, recently wrote a humorous blog post highlighting the downsides of unthoughtful decision-making and “death by meetings” on senior teams. While it’s easy to poke fun at Dilbert-like experiences that we have all participated in (and some of us even perpetuated!), there are direct correlations between poor senior team meeting management—of which loose and unintentional decision-making processes are a cornerstone—and morale of the senior-most leaders in the company. This all impacts company performance in real and tangible ways.

Research points to the importance of effective decision-making at the top of an organization and its subsequent impact on performance. RHR’s Senior Team Effectiveness survey found a remarkably strong relationship between the top team’s decision-making processes and quality1 with company performance (employee engagement, overall organizational performance, new product development, profitability/ROA, quality of products or services, sales, and revenue growth). (See Table 1).

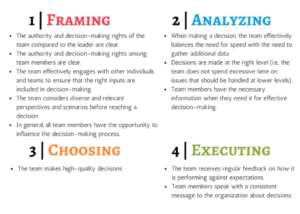

When attempting to understand how decision-making works, straightforward models work best. Utilizing a framework popularized by Dan and Chip Heath in their recent book Decisive and syncing that up with our findings, we can define what a leader can do to ensure optimal decisions get made. (See Table 2).

Framing: Defining the Problem to Be Solved or Decision to Be Made

Framing is the first step of effective decision-making and often the most misunderstood. To accurately frame the problem or decision, a leader must iteratively zoom in and zoom out until a clear definition of the problem emerges. Too often CEOs commit “narrow framing” and reduce the whole range of possible behaviors to a single binary choice (e.g., “should we pursue strategy A versus B”) before the decision process has even begun. They focus on what’s obvious and visible versus what is possible, and they can also hesitate to use their teams to help them frame a decision since it can feel unproductive and like a loss of power.

In the earliest stages of decision-making, it’s important to widen the options. “Going slow to go fast” is never more applicable than in this stage; it’s better to take the time to accurately define the scope of the problem than move too quickly and work the issue at the wrong level, making fast but suboptimal decisions. Individual conversations with trusted sources—especially the senior team—can bolster engagement of senior leaders, making them feel valued as advisors and more willing to improve the quality and ultimately execution of the decision.

Analyzing: Exploring and Analyzing Options

In the analyzing phase, leaders are faced with three primary challenges: individual cognitive biases, poor data, and dysfunctional team dynamics related to power struggles and politics. Overconfidence and confirmation biases come into play especially when leaders and teams feel a sense of urgency. They stop reality testing and seeking out disconfirming data to their impulsive conclusions. This becomes exacerbated when senior team members are jockeying for power or want to be seen in a positive light with the leader. They cease to be the reality filter for the CEO, choosing instead to eagerly support their boss to win favor.

To ensure the analyzing phase is as robust as it can be, leaders need to first ensure they are getting “good enough” data: data that is high quality and supports various points of view being raised. Second, they need to pay attention to their emotional states during analysis and their desire to come to premature closure. Lastly, they need to attend to group dynamics. One antidote can be to create roles on the team or in an advisory circle that are empowered to challenge and highlight risks or alternative scenarios.

Choosing: Making a Call or Choice

“Making a call” on a decision can be confounded by two primary reasons:

- Lack of clarity about who owns the decision. Interestingly, RACI models (clarifying who is responsible, accountable, consulted, and informed) seem to stop working at the CEO and senior executive levels since most believe they are above such processes. However, without clear ownership, fuzzy accountability prevails, and decisions can linger without action.

- Emotional churn. At times, the consequences of the decision are so large in magnitude that deciding a course of action becomes agonizing due to the potential implications of the decision.

To address the first point, if the CEO is not the accountable executive for a decision, clearly and unequivocally delegating that authority is critical. Too often senior team members are watching the unspoken cues from the boss about how she or he feels about a decision, and execution will be stalled if the CEO does not fully support the accountable executive’s authority. And to the second point, getting some distance from the decision—especially for the most impactful and weighty ones—can provide the needed perspective and courage to make the biggest calls.

Executing: Living with the Results of a Decision Made (Aligning, Communicating, and Learning)

Excessive overconfidence in the ability to execute a decision, pseudo-alignment, poor communication, and lack of tracking and learning from the previous important decisions are the primary challenges of this phase. Excessive confidence is most evident in the planning cycle where senior teams often commit to unrealistic metrics and goals. However, equally corrupting is pseudo-alignment, where team members feign agreement with a decision but fail to communicate or enforce it since it may negatively impact their area of responsibility. And given the pressures many companies feel to perform in an increasingly unpredictable and fast-changing macro environment, the concept of a learning organization has all but evaporated. There are few senior teams that actively track the execution of their decisions to see where they are succeeding and/or falling short, what they can do about that, and what they can learn.

Scenario planning is the best antidote to excessive confidence. Preparing to be wrong and having alternative paths to execute are key tools that foster agility. Having norms regarding alignment and communication can also help ensure decisions are executed. For example, “80% agreement, 100% alignment” is one such norm that CEOs can enforce with consequences for noncompliance. And keeping a placeholder at the end of each meeting for determining how a decision will be communicated is a simple yet frequently eliminated part of the decision-making process for senior teams. Lastly, establishing a norm around learning from our decisions and taking a cue from the military’s “after action review” is one way to ensure the team and organization are harvesting important lessons that will shape future decisions.

Decision-making is the cornerstone of organizational life. While the process is simple to understand, it collides with such tangibles as organizational structure, meeting management, and role clarity as well as with the intangibles of leadership, power, and cognitive biases. While our data on senior teams and decision-making demonstrates that mastering the process is worth the effort, it takes commitment from the top to make it a reality.

Table 1

* p < .05

** p < .01

Note: N = 99 senior teams for all items except The authority and decision-making rights of the team compared to the leader are clear where N = 97

Table 2

Determining which direction to take your company in is one thing; knowing how to get there is another. To learn how RHR can help your senior teams establish a clear direction and align behavior around it while enhancing your team’s ability to work together to achieve their organizational goals and create impact on the bottom line, contact Orla Leonard, Practice Leader, Senior Team Effectiveness.